Grid Investment: Repowering Scotland Poses Many Challenges

Date: 22/10/2025 | Energy & Natural Resources

There’s more than a little irony that whilst Storm Amy sent European power prices into negative territory, so many homes across Scotland were without power.

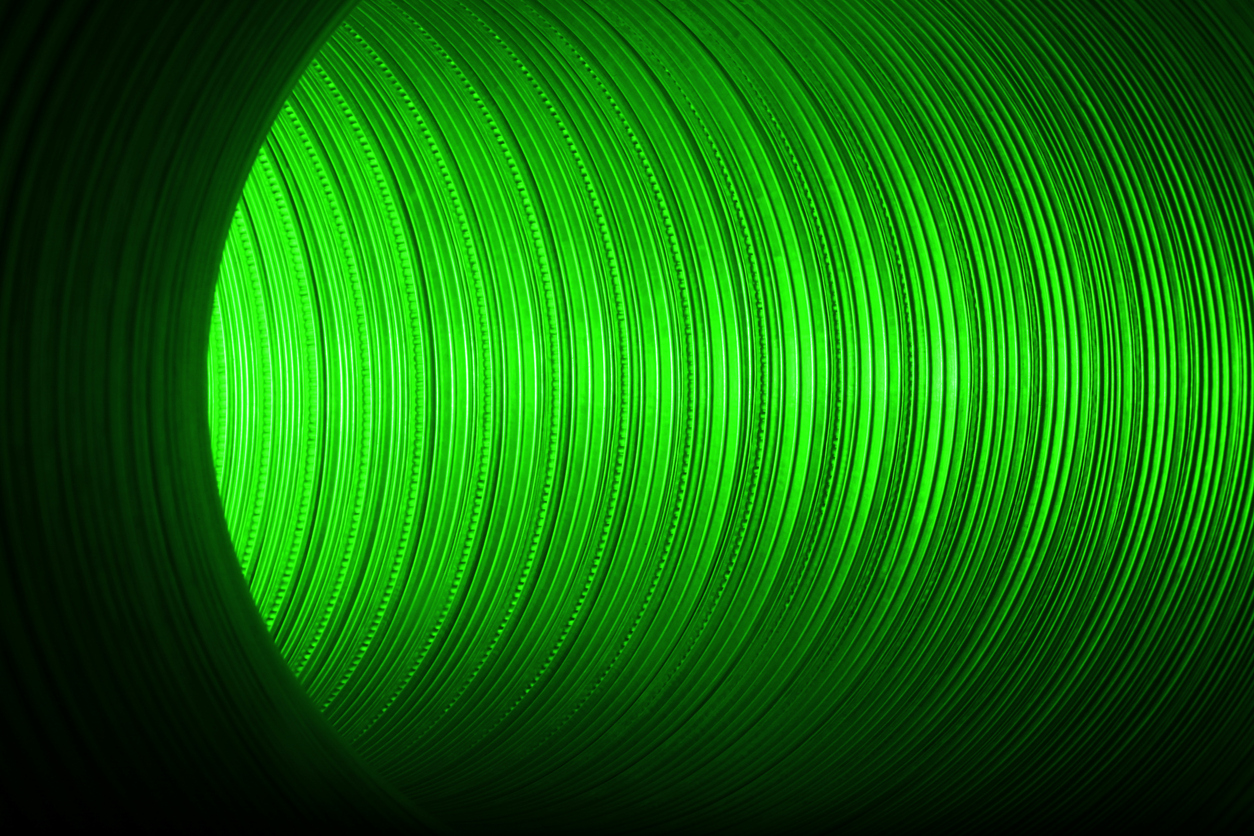

The situation reflects a lack of joined up investment in national grid infrastructure over many decades. Of course, “national grid” gives the impression the way electricity moves around the UK is part of a coherent system, when the reality is quite different.

The grid is really an aggregation of multiple localised networks drawn together into one in the 1930s, at the same time other fragmented industries such as coal were brought together under national control.

It would be wrong to suggest there’s been no investment over the intervening 100 years – far from it. However, moving electricity from where it is generated to where it is needed remains challenging. This is particularly true of renewable energy.

It is a challenge that is only going to increase, particularly as many of the original onshore wind schemes are reaching the end of their original life span.

In some cases, these schemes will be decommissioned as was envisaged 25 to 30 years ago.

That could happen for various reasons: for instance, the consenting authorities may not agree to extending existing consents or granting new ones; consent extensions or new consents may be on terms which are not economically viable or deliverable; schemes which stacked up when supported by Renewable Obligation Certificates (ROCs) may not do so in a Contracts for Difference (CfD) environment; and turbines and turbine components may be so obsolete as to be incapable of use or replacement.

It may also be that the cost of capital is too great, or the landowner is not willing to agree extension terms.

However, it seems reasonable to anticipate that many schemes will continue either in their current guise or through an entirely new, repowered scheme.

Repowering involves creating a new development on the site of the old one – almost a form of brownfield development.

It involves much larger turbines. At the turn of the Millenium, onshore turbine capacity was typically below 1MW; now it can be 5MW and greater.

That presents a range of challenges, including how to physically transport turbine infrastructure to the installation site.

Innovation can help with that, as was evidenced in 2024 when several turbine blades were transported vertically through the Scottish Borders town of Hawick.

However, it remains the fact that wind farms do not tend to be co-located with urban settlements but rather are in some of the most remote parts of the country far from ports, motorways and mainline railways.

It seems hard to see how UK and Scottish Government targets for renewable energy generation can be met without retaining existing schemes, where possible repowering them with larger and more efficient turbines, as well as new onshore and offshore schemes.

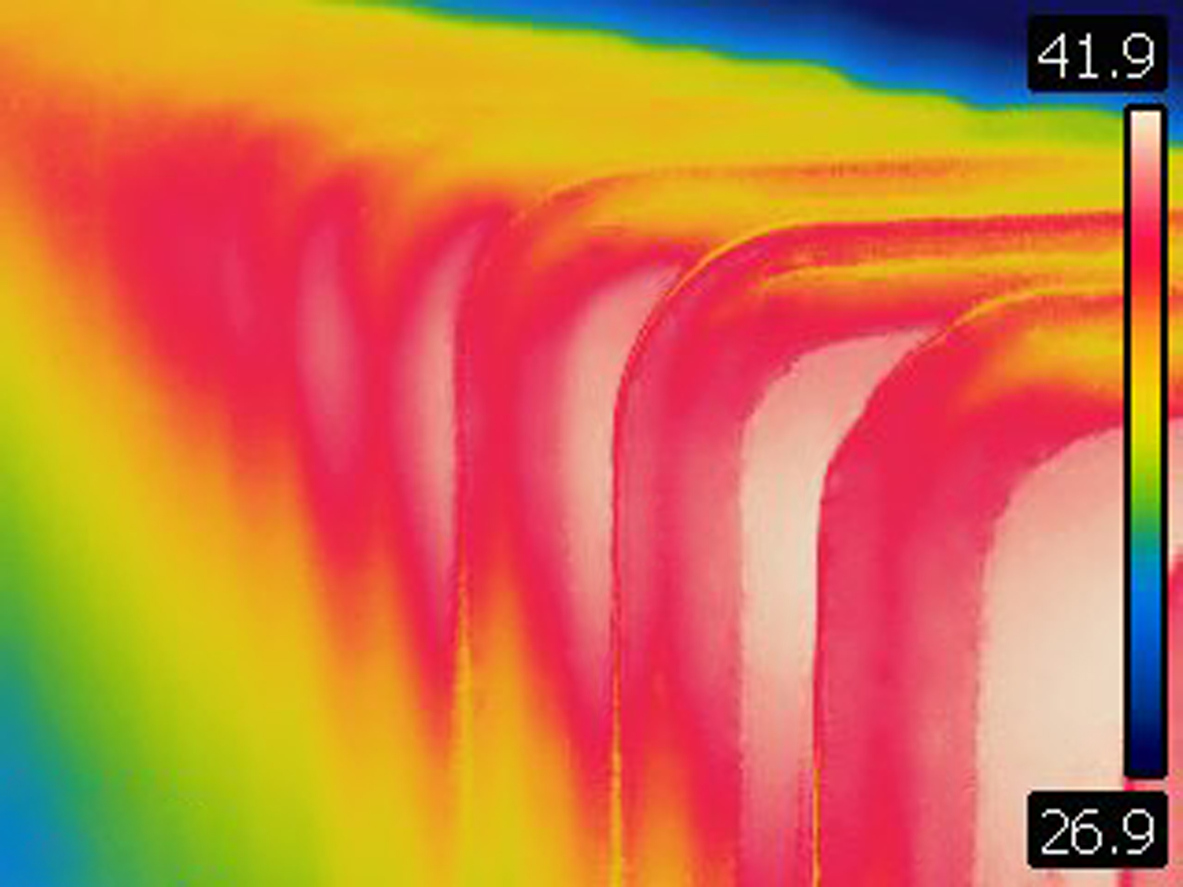

Until the national grid has the capacity to consistently accept the energy generated and to transport it to where it is needed, the system will continue to creak and not deliver the outcomes the country needs.

Government, both at Westminster and Holyrood, should be making it their priority to ensure the national grid is as good as it possibly can be and develop an industrial strategy that promotes the use of power much closer to the point of generation.

In the same way that outdated, clunky systems are a drag on a business, national infrastructure that does not meet the requirements of its end-users is a drag on the country and its economy.

This article first appeared in The Scotsman.